What is the swine flu?

Swine flu (swine influenza) is a respiratory disease caused by viruses (influenza viruses) that infect the respiratory tract of pigs, resulting in nasal secretions, a barking cough, decreased appetite, and listless behavior. Swine flu produces most of the same symptoms in pigs as human flu produces in people. Swine flu can last about one to two weeks in pigs that survive. Swine influenza virus was first isolated from pigs in 1930 in the U.S. and has been recognized by pork producers and veterinarians to cause infections in pigs worldwide. In a number of instances, people have developed the swine flu infection when they are closely associated with pigs (for example, farmers, pork processors), and likewise, pig populations have occasionally been infected with the human flu infection. In most instances, the cross-species infections (swine virus to man; human flu virus to pigs) have remained in local areas and have not caused national or worldwide infections in either pigs or humans. Unfortunately, this cross-species situation with influenza viruses has had the potential to change. Investigators decided the 2009 so-called “swine flu” strain, first seen in Mexico, should be termed novel H1N1 flu since it was mainly found infecting people and exhibits two main surface antigens, H1 (hemagglutinin type 1) and N1 (neuraminidase type1). The eight RNA strands from novel H1N1 flu have one strand derived from human flu strains, two from avian (bird) strains, and five from swine strains.

How is swine flu transmitted? Is swine flu contagious?

Swine flu is transmitted from person to person by inhalation or ingestion of droplets containing virus from people sneezing or coughing; it is not transmitted by eating cooked pork products. The newest swine flu virus that has caused swine flu is influenza A H3N2v (commonly termed H3N2v) that began as an outbreak in 2011. The “v” in the name means the virus is a variant that normally infects only pigs but has begun to infect humans. There have been small outbreaks of H1N1 since the pandemic; a recent one is in India where at least three people have died.

What is the incubation period for swine flu?

The incubation period for swine flu is about one to four days, with the average being two days; in some people, the incubation period may be as long as about seven days in adults and children.

What is the contagious period for swine flu?

The contagious period for swine flu in adults usually begins one day before symptoms develop in an adult and it lasts about five to seven days after the person becomes sick. However, people with weakened immune systems and children may be contagious for a longer period of time (for example, about 10 to 14 days).

How long does the swine flu last?

In uncomplicated infections, swine flu typically begins to resolve after three to seven days, but the malaise and cough can persist two weeks or more in some patients. Severe swine flu may require hospitalization that increases the length of time of infection to about nine to 10 days.

What causes swine flu?

The cause of the 2009 swine flu was an influenza A virus type designated as H1N1. In 2011, a new swine flu virus was detected. The new strain was named influenza A (H3N2)v. Only a few people (mainly children) were first infected, but officials from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported increased numbers of people infected in the 2012-2013 flu season. Currently, there are not large numbers of people infected with H3N2v. Unfortunately, another virus termed H3N2 (note no “v” in its name) has been detected and caused flu, but this strain is different from H3N2v. In general, all of the influenza A viruses have a structure similar to the H1N1 virus; each type has a somewhat different H and/or N structure.

Why is swine flu now infecting humans?

Many researchers now consider that two main series of events can lead to swine flu (and also avian or bird flu) becoming a major cause for influenza illness in humans.

First, the influenza viruses (types A, B, C) are enveloped RNA viruses with a segmented genome; this means the viral RNA genetic code is not a single strand of RNA but exists as eight different RNA segments in the influenza viruses. A human (or bird) influenza virus can infect a pig respiratory cell at the same time as a swine influenza virus; some of the replicating RNA strands from the human virus can get mistakenly enclosed inside the enveloped swine influenza virus. For example, one cell could contain eight swine flu and eight human flu RNA segments. The total number of RNA types in one cell would be 16; four swine and four human flu RNA segments could be incorporated into one particle, making a viable eight RNA-segmented flu virus from the 16 available segment types. Various combinations of RNA segments can result in a new subtype of virus (this process is known as antigenic shift) that may have the ability to preferentially infect humans but still show characteristics unique to the swine influenza virus (see Figure 1). It is even possible to include RNA strands from birds, swine, and human influenza viruses into one virus if a single cell becomes infected with all three types of influenza (for example, two bird flu, three swine flu, and three human flu RNA segments to produce a viable eight-segment new type of flu viral genome). Formation of a new viral type is considered to be antigenic shift; small changes within an individual RNA segment in flu viruses are termed antigenic drift (see figure 1) and result in minor changes in the virus. However, these small genetic changes can accumulate over time to produce enough minor changes that cumulatively alter the virus’ makeup over time (usually years).

Second, pigs can play a unique role as an intermediary host to new flu types because pig respiratory cells can be infected directly with bird, human, and other mammalian flu viruses. Consequently, pig respiratory cells are able to be infected with many types of flu and can function as a “mixing pot” for flu RNA segments (see figure 1). Bird flu viruses, which usually infect the gastrointestinal cells of many bird species, are shed in bird feces. Pigs can pick these viruses up from the environment, and this seems to be the major way that bird flu virus RNA segments enter the mammalian flu virus population. Figure 1 shows this process in H1N1, but the figure represents the genetic process for all flu viruses, including human, swine, and avian strains.

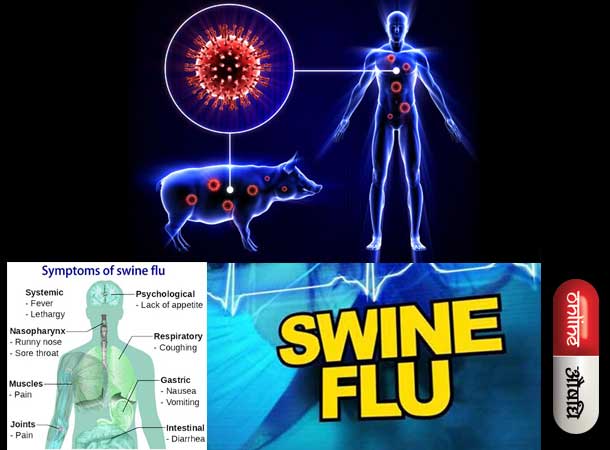

What are swine flu symptoms and signs?

Symptoms of swine flu are similar to most influenza infections: fever (100 F or greater), cough (usually dry), nasal secretions, fatigue, and headache, with fatigue being reported in most infected individuals. Some patients may also get a sore throat, rash, body (muscle) aches or pains, headaches, chills, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. In Mexico, many of the initial patients infected with H1N1 influenza were young adults, which made some investigators speculate that a strong immune response, as seen in young people, may cause some collateral tissue damage. The incubation period from exposure to first symptoms is about one to four days, with an average of two days. The symptoms last about one to two weeks and can last longer if the person has a severe infection.

Some patients develop severe respiratory symptoms, such as shortness of breath, and need respiratory support (such as a ventilator to breathe for the patient). Patients can get pneumonia (bacterial secondary infection) if the viral infection persists, and some can develop seizures. Death often occurs from secondary bacterial infection of the lungs; appropriate antibiotics need to be used in these patients. The usual mortality (death) rate for typical influenza A is about 0.1%, while the 1918 “Spanish flu” epidemic had an estimated mortality rate ranging from 2%-20%. Swine (H1N1) flu in Mexico had about 160 deaths and about 2,500 confirmed cases, which would correspond to a mortality rate of about 6%, but these initial data were revised and the mortality rate worldwide was estimated to be much lower. Fortunately, the mortality rate of H1N1 remained low and similar to that of the conventional flu (average conventional flu mortality rate is about 36,000 per year; projected H1N1 flu mortality rate was 90,000 per year in the U.S. as determined by the president’s advisory committee, but it never approached that high number).

Fortunately, although H1N1 developed into a pandemic (worldwide) flu strain, the mortality rate in the U.S. and many other countries only approximated the usual numbers of flu deaths worldwide. Speculation about why the mortality rate remained much lower than predicted includes increased public awareness and action that produced an increase in hygiene (especially hand washing), a fairly rapid development of a new vaccine, and patient self-isolation if symptoms developed.

What tests do health-care professionals use to diagnose swine flu?

Swine flu is presumptively diagnosed clinically by the patient’s history of association with people known to have the disease and their symptoms listed above. Usually, a quick test (for example, nasopharyngeal swab sample) is done to see if the patient is infected with influenza A or B virus. Most of the tests can distinguish between A and B types. The test can be negative (no flu infection) or positive for type A and B. If the test is positive for type B, the flu is not likely to be swine flu. If it is positive for type A, the person could have a conventional flu strain or swine flu. However, the accuracy of these tests has been challenged, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has not completed their comparative studies of these tests. However, a new test developed by the CDC and a commercial company reportedly can detect H1N1 reliably in about one hour; the test was formerly only available to the military. In 2010, the FDA approved a commercially available test that could detect H1N1 within four hours. Most of these rapid tests are based on PCR technology.

Swine flu is definitively diagnosed by identifying the particular antigens (surface proteins) associated with the virus type. In general, this test is done in a specialized laboratory and is not done by many doctors’ offices or hospital laboratories. However, doctors’ offices are able to send specimens to specialized laboratories if necessary. Because of the large number of novel H1N1 swine flu cases that occurred in the 2009-2010 flu season (the vast majority of flu cases [about 95%-99%] were due to novel H1N1 flu viruses), the CDC recommended only hospitalized patients’ flu virus strains be sent to reference labs to be identified. H3N2v flu strains and other flu virus strains are diagnosed by similar methods.

What types of doctors treat swine flu?

Almost all uncomplicated patients with swine flu can be treated at home or by the patient’s pediatrician, primary-care provider, or emergency-medicine doctor. For more complicated and/or severe swine flu infections, specialists such as critical-care specialists, lung specialists (pulmonologists), and infectious-disease specialists may be consulted.

What is the treatment for swine flu?

The best treatment for influenza infections in humans is prevention by vaccination. Work by several laboratories has produced vaccines. The first H1N1 vaccine released in early October 2009 was a nasal spray vaccine that was approved for use in healthy individuals ages 2-49. The injectable vaccine, made from killed H1N1, became available in the second week of Oct. 2009. This vaccine was approved for use in ages 6 months to the elderly, including pregnant females. Both of these vaccines were approved by the CDC only after they had conducted clinical trials to prove that the vaccines were safe and effective. A new influenza vaccine preparation is the intradermal (trivalent) vaccine is available; it works like the shot except the administration is less painful. It is approved for ages 18-64 years.

Almost all vaccines have some side effects. Common side effects of H1N1 vaccines (alone or in combination with other flu viral strains) are typical of flu vaccines used over many years and are as follows:

- Flu shot: Soreness, redness, minor swelling at the shot site, muscle aches, low-grade fever, and nausea do not usually last more than about 24 hours.

- Nasal spray: runny nose, low-grade fever, vomiting, headache, wheezing, cough, and sore throat

- Intradermal shot: redness, swelling, pain, headache, muscle aches, fatigue

The flu shot (vaccine) is made from killed virus particles so a person cannot get the flu from a flu shot. However, the nasal spray vaccine contains live virus that have been altered to hinder its ability to replicate in human tissue. People with a suppressed immune system should not get vaccinated with the nasal spray. Also, most vaccines that contain flu viral particles are cultivated in eggs, so individuals with an allergy to eggs should not get the vaccine unless tested and advised by their doctor that they are cleared to obtain it. Like all vaccines, rare events may occur in some rare cases (for example, swelling, weakness, or shortness of breath). About one person in a million who gets the vaccine may develop a neurological problem termed Guillain-Barré syndrome, which can cause weakness or paralysis, difficulty breathing, bladder and/or bowel problems, and other nerve problems. If any symptoms like these develop, see a physician immediately.

Two antiviral agents have been reported to help prevent or reduce the effects of swine flu. They are zanamivir (Relenza) and oseltamivir (Tamiflu), both of which are also used to prevent or reduce influenza A and B symptoms. These drugs should not be used indiscriminately, because viral resistance to them can and has occurred. Also, they are not recommended if the flu symptoms already have been present for 48 hours or more, although hospitalized patients may still be treated past the 48-hour guideline. Severe infections in some patients may require additional supportive measures such as ventilation support and treatment of other infections like pneumonia that can occur in patients with a severe flu infection. The CDC has suggested in their guidelines that pregnant females can be treated with the two antiviral agents.

On Dec. 22, 2014, the FDA approved the first new anti-influenza drug (for H1N1 and other influenza virus types) in 15 years, peramivir injection (Rapivab). It is approved for use in the following settings:

Diarrhea, skin infections, hallucinations, and/or altered behavior may occur as side effects of this drug.

- Adult patients for whom therapy with an intravenous (IV) medication is clinically appropriate, based upon one or more of the following reasons:

- The patient is not responding to either oral or inhaled antiviral therapy, or

- drug delivery by a route other than IV is not expected to be dependable or is not feasible, or

- the physician decides that IV therapy is appropriate due to other circumstances.

- Pediatric patients for whom an intravenous medication clinically appropriate because:

- The patient is not responding to either oral or inhaled antiviral therapy, or

- drug delivery by a route other than IV is not expected to be dependable or is not feasible.

What are the risk factors for swine flu?

Vaccination to prevent influenza is particularly important for people who are at increased risk for severe complications from influenza or at higher risk for influenza-related doctor or hospital visits. When vaccine supply is limited, vaccination efforts should focus on delivering vaccination to the following people since these populations have a higher risk for H1N1 and some other viral infections according to the CDC:

- All children 6 months to 4 years (59 months) of age

- All people 50 years of age and older

- Adults and children who have chronic pulmonary (including asthma) or cardiovascular (except isolated hypertension), renal, hepatic, neurological, hematologic, or metabolic disorders (including diabetes mellitus)

- People who have immunosuppression (including immunosuppression caused by medications or by HIV)

- Women who are or will be pregnant during the influenza season

- Children and adolescents (6 months to 18 years of age) who are receiving long-term aspirin therapy and who might be at risk for experiencing Reye’s syndrome after influenza virus infection

- Residents of nursing homes and other long-term-care facilities

- American Indians/Alaska natives

- People who are morbidly obese (BMI ≥40)

- Health-care professionals (doctors, nurses, health-care personnel treating patients)

- Household contacts and caregivers of children under 5 years of age and adults 50 years of age and older, with particular emphasis on vaccinating contacts of children less than 6 months age

- Household contacts and caregivers of people with medical conditions that put them at higher risk for severe complications from influenza

Are there home remedies for swine flu?

There are many flu “cures” and “treatments” described on the Internet (for example, how cayenne pepper, menthol, or ginseng can be used to treat the flu); before using any of these substances, check with a doctor. However, there are many over-the-counter medications, such as naproxen (Aleve), ibuprofen (Advil and others) and acetaminophen (Tylenol), to reduce fever and discomfort, lozenges to sooth a sore throat, and decongestants to help manage mucus production and coughing. These medications help manage flu symptoms but do not cure the viral disease.

Was swine flu (H1N1) a cause of an epidemic or pandemic in the 2009-2010 flu season?

Yes. An epidemic is defined as an outbreak of a contagious disease that is rapid and widespread, affecting many individuals at the same time. The swine flu outbreak in Mexico fit this definition. A pandemic is an epidemic that becomes so widespread that it affects a region, continent, or the world. On June 11, 2009, WHO officials determined that H1N1 2009 influenza A swine flu reached WHO level 6 criteria (person-to-person transmission in two separate WHO-determined world regions) and declared the first flu pandemic in 41 years. The H1N1 flu reached over 200 different countries on every continent except Antarctica in the 2009-2010 flu season; fortunately, the severity of the disease did not increase. The following is the CDC data for mortality and morbidity of the 2009 epidemic in the US: final estimates were published in 2011 and state that from Apr. 12, 2009, to Apr. 10, 2010 approximately 60.8 million cases (range: 43.3-89.3 million), 274,304 hospitalizations (195,086-402,719), and 12,469 deaths (8868-18,306) occurred in the United States due to H1N1. An outbreak in India that became widespread in that country is still ongoing in 2016.

What is the prognosis (outlook) and complications for patients who get swine flu?

In general, the majority (about 90%-95%) of people who get the disease feel terrible (see symptoms) but recover with no problems, as seen in patients in Mexico, the U.S., and many other countries.

People with suppressed immune systems historically have worse outcomes than uncompromised individuals; investigators suspect that as swine flu spreads, the mortality rates may rise and be high in this population. Current data suggest that pregnant individuals, children under 2 years of age, young adults, and individuals with any immune compromise or debilitation are likely to have a worse prognosis. Complications of swine flu may resemble severe viral pneumonia or the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome caused by a coronavirus strain) outbreak in 2002-2003 in which the disease spread to about 10 countries with over 7,000 cases, caused over 700 deaths, and had a 10% mortality rate. At the beginning of the pandemic, the numbers of people with flu-like illness were higher than usual and the illness initially affected a much younger population than the conventional flu. As the pandemic progressed, more young children became infected than usual, but the mortality statistics became more similar to the conventional flu mortality rate, with an older population (especially ages 50-64) having the highest death rate. Pneumonia (viral and secondary bacterial pneumonia), is the most serious complication of the flu as it can cause death. Other complications include sinus and ear infections, asthma exacerbations, and/or bronchitis.

Reference : medicinenet.com